Year of birth and death of Alexander 2. Biography of Emperor Alexander II Nikolaevich. Assassination attempts on Alexander II

Russian Emperor Alexander II was born on April 29 (17 old style), 1818 in Moscow. The eldest son of the Emperor and Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. After his father's accession to the throne in 1825, he was proclaimed heir to the throne.

Received an excellent education at home. His mentors were lawyer Mikhail Speransky, poet Vasily Zhukovsky, financier Yegor Kankrin and other outstanding minds of that time.

He inherited the throne on March 3 (February 18, old style) 1855 at the end of an unsuccessful campaign for Russia, which he managed to complete with minimal losses for the empire. He was crowned king in the Assumption Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin on September 8 (August 26, old style) 1856.

On the occasion of the coronation, Alexander II declared an amnesty for the Decembrists, Petrashevites, and participants in the Polish uprising of 1830-1831.

The transformations of Alexander II affected all spheres of Russian society, shaping the economic and political contours of post-reform Russia.

On December 3, 1855, by imperial decree, the Supreme Censorship Committee was closed and discussion of government affairs became open.

In 1856, a secret committee was organized “to discuss measures to organize the life of the landowner peasants.”

On March 3 (February 19, old style), 1861, the emperor signed the Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom and the Regulations on peasants emerging from serfdom, for which they began to call him the “tsar-liberator.” The transformation of peasants into free labor contributed to the capitalization of agriculture and the growth of factory production.

In 1864, by issuing the Judicial Statutes, Alexander II separated the judicial power from the executive, legislative and administrative powers, ensuring its complete independence. The process became transparent and competitive. The police, financial, university and entire secular and spiritual educational systems as a whole were reformed. The year 1864 also marked the beginning of the creation of all-class zemstvo institutions, which were entrusted with the management of economic and other social issues locally. In 1870, on the basis of the City Regulations, city councils and councils appeared.

As a result of reforms in the field of education, self-government became the basis of the activities of universities, and secondary education for women was developed. Three Universities were founded - in Novorossiysk, Warsaw and Tomsk. Innovations in the press significantly limited the role of censorship and contributed to the development of the media.

By 1874, Russia had rearmed its army, created a system of military districts, reorganized the Ministry of War, reformed the officer training system, introduced universal military service, reduced the length of military service (from 25 to 15 years, including reserve service), and abolished corporal punishment. .

The emperor also established the State Bank.

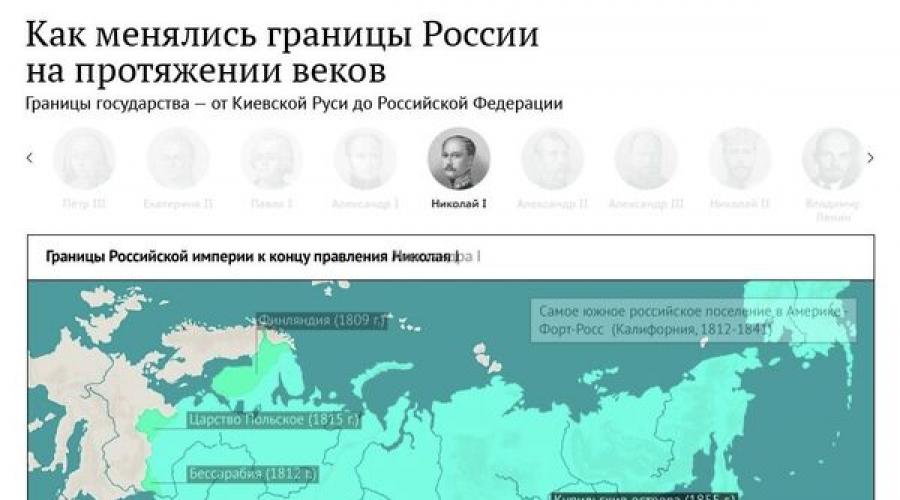

The internal and external wars of Emperor Alexander II were victorious - the uprising that broke out in Poland in 1863 was suppressed, and the Caucasian War (1864) ended. According to the Aigun and Beijing treaties with the Chinese Empire, Russia annexed the Amur and Ussuri territories in 1858-1860. In 1867-1873, the territory of Russia increased due to the conquest of the Turkestan region and the Fergana Valley and the voluntary entry into vassal rights of the Bukhara Emirate and the Khanate of Khiva. At the same time, in 1867, the overseas possessions of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands were ceded to the United States, with which good relations were established. In 1877, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Türkiye suffered a defeat, which predetermined the state independence of Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and Montenegro.

© Infographics

© Infographics

The reforms of 1861-1874 created the preconditions for a more dynamic development of Russia and strengthened the participation of the most active part of society in the life of the country. The flip side of the transformations was the aggravation of social contradictions and the growth of the revolutionary movement.

Six attempts were made on the life of Alexander II, the seventh was the cause of his death. The first shot was shot by nobleman Dmitry Karakozov in the Summer Garden on April 17 (4 old style), April 1866. By luck, the emperor was saved by the peasant Osip Komissarov. In 1867, during a visit to Paris, Anton Berezovsky, a leader of the Polish liberation movement, attempted to assassinate the emperor. In 1879, the populist revolutionary Alexander Solovyov tried to shoot the emperor with several revolver shots, but missed. The underground terrorist organization "People's Will" purposefully and systematically prepared regicide. Terrorists carried out explosions on the royal train near Alexandrovsk and Moscow, and then in the Winter Palace itself.

The explosion in the Winter Palace forced the authorities to take extraordinary measures. To fight the revolutionaries, a Supreme Administrative Commission was formed, headed by the popular and authoritative General Mikhail Loris-Melikov at that time, who actually received dictatorial powers. He took harsh measures to combat the revolutionary terrorist movement, while at the same time pursuing a policy of bringing the government closer to the “well-intentioned” circles of Russian society. Thus, under him, in 1880, the Third Department of His Imperial Majesty’s Own Chancellery was abolished. Police functions were concentrated in the police department, formed within the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

On March 14 (old style 1), 1881, as a result of a new attack by Narodnaya Volya, Alexander II received mortal wounds on the Catherine Canal (now the Griboyedov Canal) in St. Petersburg. The explosion of the first bomb thrown by Nikolai Rysakov damaged the royal carriage, wounded several guards and passers-by, but Alexander II survived. Then another thrower, Ignatius Grinevitsky, came close to the Tsar and threw a bomb at his feet. Alexander II died a few hours later in the Winter Palace and was buried in the family tomb of the Romanov dynasty in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg. At the site of the death of Alexander II in 1907, the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood was erected.

In his first marriage, Emperor Alexander II was with Empress Maria Alexandrovna (nee Princess Maximiliana-Wilhelmina-Augusta-Sophia-Maria of Hesse-Darmstadt). The emperor entered into a second (morganatic) marriage with Princess Ekaterina Dolgorukova, bestowed with the title of Most Serene Princess Yuryevskaya, shortly before his death.

The eldest son of Alexander II and heir to the Russian throne, Nikolai Alexandrovich, died in Nice from tuberculosis in 1865, and the throne was inherited by the emperor's second son, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich (Alexander III).

The material was prepared based on information from open sources

Alexander I was born in 1818 on April 29, in Moscow. In honor of his birth, a salvo of 201 cannons was fired in Moscow. The birth of Alexander II occurred during the reign of Alexander I, who had no children, and Alexander I’s first brother Constantine had no imperial ambitions, which is why the son of Nicholas I, Alexander II, was immediately considered as the future emperor. When Alexander II was 7 years old, his father had already become emperor.

Nicholas I took a very responsible approach to his son’s education. Alexander received an excellent education at home. His teachers were outstanding minds of that time, such as lawyer Mikhail Speransky, poet Vasily Zhukovsky, financier Yegor Kankrin and others. Alexander studied the Law of God, legislation, foreign policy, physical and mathematical sciences, history, statistics, chemistry and technology. In addition, he studied military sciences. Mastered English, German and French. The poet Vasily Zhukovsky, who was also Alexander’s teacher of the Russian language, was appointed as the teacher of the future emperor.

Alexander II in his youth. Unknown artist. OK. 1830

Alexander's father personally supervised his education, attending Alexander's exams, which he himself organized every two years. Nicholas also involved his son in government affairs: from the age of 16, Alexander had to attend meetings of the Senate, and later Alexander became a member of the Synod. In 1836, Alexander was promoted to major general and included in the tsar's retinue.

The training ended with a trip to the Russian Empire and Europe.

Nicholas I, from the “admonition” to his son before his trip to Russia: “Your first duty will be to see everything with the indispensable goal of becoming thoroughly familiar with the state over which sooner or later you are destined to reign. Therefore, your attention should be equally directed to everything... in order to gain an understanding of the present state of affairs.”

In 1837, Alexander, in the company of Zhukovsky, adjutant Kavelin and several other people close to him, made a long trip around Russia and visited 29 provinces of the European part, Transcaucasia and Western Siberia.

Nicholas I, from the “admonition” to his son before his trip to Europe: “Many things will seduce you, but upon closer examination you will be convinced that not everything deserves imitation; ... we must always preserve our nationality, our imprint, and woe to us if we fall behind it; in him is our strength, our salvation, our uniqueness.”

In 1838-1839, Alexander visited the countries of Central Europe, Scandinavia, Italy and England. In Germany, he met his future wife, Maria Alexandrovna, daughter of Grand Duke Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt, with whom they married two years later.

Beginning of the Reign

The throne of the Russian Empire went to Alexander on March 3, 1855. During this difficult time for Russia, the Crimean War, in which Russia had no allies, and the adversaries were advanced European powers (Turkey, France, England, Prussia and Sardinia). The war for Russia at the time of Alexander’s accession to the throne was almost completely lost. Alexander's first important step was to reduce the country's losses to a minimum by concluding the Treaty of Paris in 1856. Afterwards, the emperor visited France and Poland, where he made calls to “stop dreaming” (meaning dreams of the defeat of Russia), and later entered into an alliance with the King of Prussia, forming a “dual alliance.” Such actions greatly weakened the foreign policy isolation of the Russian Empire, in which it was located during the Crimean War.

However, the problem of war was not the only one that the new emperor inherited from the hands of his late father: the peasant, Polish and eastern issues were not resolved. In addition, the country's economy was severely depleted by the Crimean War.

Nicholas I, before his death, addressing his son: “I’m handing over my team to you, but, unfortunately, not in the order I wanted, leaving you with a lot of work and worries.”

Period of Great Reforms

Initially, Alexander supported his father's conservative policies, but long-standing problems could no longer remain unresolved and Alexander began a policy of reform.

In December 1855, the Supreme Censorship Committee was closed and the free issuance of foreign passports was allowed. In the summer of 1856, on the occasion of the coronation, the new emperor granted amnesty to the Decembrists, Petrashevites (freethinkers who were going to rebuild the political system in Russia, arrested by the government of Nicholas I) and participants in the Polish uprising. A “thaw” has set in in the socio-political life of the country.

In addition, Alexander II liquidated in 1857 military settlements, established under Alexander I.

The next thing was the solution to the peasant question, which greatly hampered the development of capitalism in the Russian Empire and every year the gap with the advanced European powers increased.

Alexander II, from an address to the nobles in March 1856: “There are rumors that I want to announce the liberation of serfdom. This is not fair... But I won’t tell you that I am completely against it. We live in such an age that in time this must happen... It is much better for it to happen from above than from below

The reform of this phenomenon was prepared long and carefully, and only in 1861 Alexander II signed Manifesto on the abolition of serfdom And Regulations on peasants emerging from serfdom, compiled by proxies of the emperors, mostly liberals such as Nikolai Milyutin, Yakov Rostovtsev and others. However, the liberal spirit of the reform developers was suppressed by the nobility, who for the most part did not want to be deprived of any personal benefits. For this reason, the reform was carried out more in the interests of the nobility than in the interests of the people, since the peasants received only personal freedom and civil rights, and they had to buy land from the landowners for the needs of the peasants. Nevertheless, the government helped the peasants with the redemption with subsidies, which allowed the peasants to immediately buy the land while remaining debtors to the state. Despite these aspects, Alexander II was immortalized in history as the “Tsar Liberator” for this reform.

Reading of the 1861 Manifesto by Alexander II on Smolnaya Square in St. Petersburg. Artist A.D. Kivshenko.

The reform of serfdom was followed by a number of reforms. The abolition of serfdom created a new type of economy, while finance built on the feudal system reflected an outdated type of its development. In 1863, Financial Reform was carried out. In the process of this reform, the State Bank of the Russian Empire and the Main Redemption Institution under the Ministry of Finance were created. The first step was the emergence of the principle of transparency in the formation of the state budget, which made it possible to minimize embezzlement. Treasuries were also created to administer all government revenues. Taxation after the reform began to resemble modern taxation, with taxes divided into direct and indirect.

In 1863, an education reform was carried out, which made secondary and higher education accessible, a network of public schools was created, and schools for commoners were created. Universities received a special status and relative autonomy, which in turn had a positive impact on the conditions of scientific activity and the prestige of the teaching profession.

The next major reform was Zemstvo reform carried out in July 1864. According to this reform, local self-government bodies were created: zemstvos and city dumas, which themselves resolved economic and budgetary issues.

There was a need for a new judicial system to govern the country. Judicial reform was also carried out in 1864, which guaranteed the equality of all classes before the law. The institution of juries was created. Also, most of the meetings became open and public. All meetings became competitive.

In 1874, military reform was carried out. This reform was motivated by the humiliating defeat of Russia in the Crimean War, where all the shortcomings of the Russian army and its lag behind the European ones surfaced. It provided transition from conscription to universal conscription and reduction of service periods. As a result of the reform, the size of the army was reduced by 40%, a network of military and cadet schools was created for people from all classes, the General Headquarters of the army and military districts were created, the rearmament of the army and navy, the abolition of corporal punishment in the army and the creation of military courts and military prosecutors with adversarial litigation.

Historians have noted that Alexander II made decisions about reforms not because of his own convictions, but because of his understanding of their necessity. So we can conclude that for Russia of that era they were forced.

Territorial changes and wars under Alexander II

Internal and external wars during the reign of Alexander II were successful. The Caucasian War ended successfully in 1864, as a result of which the entire North Caucasus was captured by Russia. According to the Aigun and Beijing treaties with the Chinese Empire, Russia annexed the Amur and Ussuri territories in 1858-1860. In 1863, the emperor successfully suppressed the uprising in Poland. In 1867-1873, the territory of Russia increased due to the conquest of the Turkestan region and the Fergana Valley and the voluntary entry into vassal rights of the Bukhara Emirate and the Khanate of Khiva.

In 1867, Alaska (Russian America) was sold to the United States for $7 million. Which at that time was a profitable deal for Russia due to the remoteness of these territories and for the sake of good relations with the United States.

Growing dissatisfaction with the activities of Alexander II, assassination attempts and murder

During the reign of Alexander II, unlike his predecessors, there were more than enough social protests. Numerous peasant uprisings (of peasants dissatisfied with the conditions of the peasant reform), the Polish uprising and, as a consequence, the emperor’s attempts to Russify Poland led to waves of discontent. In addition, numerous protest groups appeared among the intelligentsia and workers, forming circles. Numerous circles began to propagate revolutionary ideas by “going to the people.” The government's attempts to take control of these processes only worsened the process. For example, in the process of 193 populists, society was outraged by the actions of the government.

“In general, in all segments of the population, some kind of vague displeasure has overwhelmed everyone. Everyone is complaining about something and seems to want and expect change.”

Assassinations and terror of significant government officials spread. While the public literally applauded the terrorists. Terrorist organizations grew more and more; for example, Narodnaya Volya, which sentenced Alexander II to death by the end of the 70s, had more than a hundred active members.

Plason Anton-Antonovich, contemporary of Alexander II: “Only during an armed uprising that has already flared up can there be the kind of panic that gripped everyone in Russia at the end of the 70s and in the 80s. Throughout Russia, everyone fell silent in clubs, in hotels, on the streets and in bazaars... And both in the provinces and in St. Petersburg, everyone was waiting for something unknown, but terrible, no one was sure of the future.”

Alexander II literally did not know what to do and was completely at a loss. In addition to public discontent, the emperor had problems in his family: in 1865, his eldest son Nicholas died, his death undermined the health of the empress. As a result, there was complete alienation in the emperor's family. Alexander came to his senses a little when he met Ekaterina Dolgorukaya, but this relationship also caused censure from society.

Head of Government Pyotr Valuev: “The Emperor looks tired and himself spoke of nervous irritation, which he is trying to hide. Crowned half-ruin. In an era where strength is needed, obviously one cannot count on it.”

Osip Komissarov. Photo from the collection of M.Yu. Meshchaninov

The first attempt on the tsar’s life was carried out on April 4, 1866 by a member of the “Hell” society (a society adjacent to the “People and Freedom” organization) Dmitry Karakozov; he tried to shoot the tsar, but at the moment of the shot he was pushed by the peasant Osip Komisarov (later a hereditary nobleman).

“I don’t know what, but my heart somehow beat especially when I saw this man hastily making his way through the crowd; I involuntarily watched him, but then, however, forgot him when the sovereign approached. Suddenly I saw that he had taken out and was aiming a pistol: it instantly seemed to me that if I rushed at him or pushed his hand to the side, he would kill someone else or me, and I involuntarily and forcefully pushed his hand up; Then I don’t remember anything, I felt like I was in a fog.”

The second attempt was carried out in Paris on May 25, 1867 by Polish emigrant Anton Berezovsky, but the bullet hit a horse.

On April 2, 1879, a member of Narodnaya Volya, Alexander Solovyov, fired 5 shots at the emperor from a distance of 10 steps, when he was walking around the Winter Palace without guards or escort, but not a single bullet hit the target.

On November 19 of the same year, members of Narodnaya Volya unsuccessfully attempted to mine the Tsar's train. Luck smiled on the emperor again.

On February 5, 1880, the People's Will member Stepan Khalturin blew up the Winter Palace, but only soldiers from his personal guard were killed, the emperor himself and his family were not injured.

Photo of the halls of the Winter Palace after the explosion.

Alexander II died on March 1, 1881, an hour after another assassination attempt from the explosion of a second bomb thrown at his feet on the embankment of the Catherine Canal in St. Petersburg by Narodnaya Volya member Ignatius Grinevitsky. The emperor died on the day when he intended to approve Loris-Melikov’s constitutional project.

Results of the reign

Alexander II went down in history as the “tsar-liberator” and reformer, although the reforms carried out did not completely solve many of Russia’s centuries-old problems. The country's territory expanded significantly, despite the loss of Alaska.

However, the economic condition of the country deteriorated under him: industry plunged into depression, public and foreign debt reached large sizes, and a foreign trade deficit formed, which led to a breakdown in finances and monetary relations. Society was already turbulent, and by the end of the reign a complete split had formed in it.

Personal life

Alexander II often spent time abroad, was a passionate lover of hunting large animals, loved ice skating and greatly popularized this phenomenon. I myself suffered from asthma.

He himself was a very amorous person; during a trip to Europe after his studies, he fell in love with Queen Victoria.

He was married twice. From his first marriage to Maria Alexandrovna (Maximilian of Hesse) he had 8 children, including Alexander III. From his second marriage to Ekaterina Dolgorukova he had 4 children.

Family of Alexander II. Photo by Sergei Levitsky.

In memory of Alexander II, the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood was erected at the site of his death.

April 29, 1818, born 190 years ago Alexander Nikolaevich Romanov, who in the history of Russia remained the emperor Alexander II Liberator. During his reign, significant reforms took place: peasant, zemstvo, judicial, urban and military. Descendants will always associate the name of Alexander II with February 19, 1861 - the day of the abolition of serfdom. It is unknown what the future fate of the Russian Empire would have been like if he had managed to promulgate the draft Constitution. But the day before this event, the emperor was killed by the terrorist Grinevitsky.

Personal data

Alexander Nikolaevich Romanov was born on April 29 (17), 1818, on Bright Wednesday, at 11 a.m. in the Bishop's House of the Chudov Monastery of the Moscow Kremlin, where the entire imperial family arrived in early April for fasting and celebrating Easter. In honor of the birth of the heir to the throne, Moscow was given a salute of 201 cannon salvos, and on May 5, the sacraments of baptism and confirmation were performed in the Church of the Chudov Monastery by Moscow Archbishop Augustine, after which a gala dinner was given by Empress Maria Feodorovna.

The future emperor was educated at home. His mentor (with the responsibility of supervising the entire process of upbringing and education) was Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky, the teacher of the Law of God and Sacred History - Archpriest Gerasim Pavsky (until 1835), the military instructor - Karl Karlovich Merder, as well as: Mikhail Mikhailovich Speransky (legislation ), Konstantin Ivanovich Arsenyev (statistics and history), Egor Frantsevich Kankrin (finance), Academician Collins (arithmetic), Karl-Bernhard Antonovich Trinius (natural history).

According to numerous testimonies, the future emperor was very impressionable and amorous in his youth. So, during a trip to London in 1839, he developed a fleeting but strong love for the young Queen Victoria, who would later become for him the most hated ruler in Europe. Upon reaching adulthood on April 22, 1834 (the day he took the oath), the heir-cresarevich was introduced by his father to the main state institutions of the Empire: in 1834 - to the Senate, in 1835 - to the Holy Governing Synod; from 1841 - member of the State Council, from 1842 - member of the Committee of Ministers. In 1837, Alexander made a long trip around the country and visited 29 provinces of the European part of Russia, Transcaucasia and Western Siberia, and in 1838-39 he visited Europe. The military service of the future emperor was quite successful. In 1836 he already became a major general, in 1844 - a full general, commanding the guards infantry. Since 1849, Alexander was the head of military educational institutions, chairman of the Secret Committees on Peasant Affairs of 1846-1848. During the Crimean War of 1853-56, with the declaration of martial law in the St. Petersburg province, he commanded all the troops of the capital.

Work history

Emperor Alexander II ascended the throne on February 19, 1855, during one of the most difficult moments Russia had ever experienced. “I hand over my command to you, but, unfortunately, not in the order I wanted, leaving you with a lot of work and worries,” Nicholas I told him as he died. Indeed, the political and military situation in Russia at that time was close to catastrophic .

After the lost Crimean War of 1853-1856. all levels of society demanded change. It was then that the terms “thaw” and “glasnost” appeared. The Supreme Censorship Committee was closed, and discussion of government affairs became open. A polyamnesty was announced for the Decembrists, Petrashevites, and participants in the Polish uprising of 1830-1831. But the main issue remained the peasant one. In 1856, a secret committee was organized “to discuss measures to organize the life of the landowner peasants.” Alexander II addressed a speech to representatives of the nobles of the Moscow province: “The existing order of ownership of souls cannot remain unchanged. It is better to begin to destroy serfdom from above, rather than wait for the time when it begins to be destroyed of its own accord from below.” Overcoming the opposition of opponents of the reform, Alexander II was contradictory and inconsistent, and yet the Editorial Commissions managed to develop the basis of the “Regulations of February 19, 1861.” This reform failed to resolve the issues of either land ownership or personal rights of peasants. During the reign of Alexander II, the following reforms were also carried out: university (1863), judicial (1864), press (1865), military (1874); self-government was introduced in zemstvos (1864) and cities (1870). The “revolution from above,” which had a bourgeois character, was not only not consistent, but also could not reach its logical conclusion - a constitution. As a result, Alexander II becomes a target for terrorist revolutionaries (he survived six assassination attempts in total), which, in turn, contributed to the transition to protective principles in government policy, in particular, to strengthening the role of the III Department, headed by P.A. Shuvalov. The changes in Alexander II’s mood were also influenced by events in his personal life. In April 1865, Alexander suffered a severe blow both as a man and as an emperor. In Nice, his eldest son Nikolai, a young man who had just turned 21, had successfully completed his education, found a bride, and intended to begin government activity as an assistant and future successor to his father, died of spinal meningitis. The emperor's second son, Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich, was declared the new heir to the throne. Both in terms of abilities and education, he frankly did not correspond to his high purpose. Alexander II became apathetic and lost interest in state affairs. In the field of foreign policy, Alexander II sought to expand the empire and strengthen Russian influence. He contributed to the liberation of Bulgaria from the Ottoman yoke (1877-1878), went to the active army and left it only after the fall of Plevna, which predetermined the outcome of the war. Having won a military victory, Russia suffered a diplomatic defeat at the Berlin Congress in 1878. This war, which played a beneficial role for the southern Slavs and raised the military prestige of Russia, disrupted the implementation of the necessary monetary and exchange rate reform and thereby increased confrontation in society. The conquest and then the peaceful development of vast territories of Central Asia were successful. According to the agreements concluded with China, the Ussuri region was recognized as Russian territory.

On March 1, 1881, the Tsar was mortally wounded by the terrorist Grinevitsky. Alexander was killed on the very day when he was supposed to sign the draft of a broad program of administrative and economic reforms developed by M.T. Loris-Melikov.

Information about relatives

Father - Nicholas I (1796-1855), emperor since 1825, third son Emperor Paul I, honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences (1826). He ascended the throne after the sudden death of his brother - Emperor Alexander I. Suppressed the Decembrist uprising. Under Nicholas I, the centralization of the bureaucratic apparatus was strengthened, the Third Department was created, the Complete Collection of Laws was published and the Code of Laws of the Russian Empire was compiled, and new censorship regulations were introduced (1826, 1828). Secret committees were repeatedly convened to discuss the issue of abolishing serfdom, but their work had no consequences. In 1837, traffic was opened on the first Tsarskoye Selo railway in Russia. The Polish uprising of 1830-1831 and the revolution in Hungary of 1848-1849 were suppressed. An important aspect of foreign policy was the return to the principles of the Holy Alliance. During the reign of Nicholas I, Russia took part in the Caucasian wars (1817-1864), Russian-Persian (1826-1828), Russian-Turkish (1828-1829), Crimean (1853-1856). Defeat in the last war became the reason for the reforms of the 1860-70s, carried out by Alexander II.

Mother - Alexandra Feodorovna (nee Princess Friederike Charlotte Wilhelmina, also known as Charlotte of Prussia). Friederike Charlotte Wilhelmina was born on July 13, 1798, the third child of Prussian King Frederick William III and his wife, Queen Louise. She was the sister of the Prussian kings Frederick William IV and Wilhelm I, later the first German emperor. On July 13, 1817, she married the brother of Russian Emperor Alexander I, Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich. Marriage presupposed the transition of the bride to the Orthodox confession and the naming of a new name, which is available in the Orthodox calendar. The marriage pursued primarily political goals: strengthening the political union of Russia and Prussia, but it turned out to be happy and with many children. After her husband's accession to the throne in 1825, Alexandra Feodorovna became the Russian Empress.

Personal life

The personal life of Alexander II was always full of bright novels and unforgettable hobbies. This handsome man broke more than one hundred women's hearts. Two women became truly significant in the life of the emperor.

Alexander's first wife was the daughter of the Grand Duke of Hesse, Louis II, whose maiden name was Maximilian-Wilhelmina-Augusta-Sophia-Maria. The future emperor, traveling during his time as crown prince in Western Europe (1838-1839), according to the attraction of his heart, chose Mary as his friend in life. In the summer of 1840 she arrived in Russia; On April 16, 1841 the marriage took place. Maria Alexandrovna gave birth to Alexandra two daughters, Alexandra and Maria, and six sons: Nicholas, Alexander (who became Emperor of Russia after his father), Vladimir, Alexei, Sergei and Pavel.

Alexander first saw his second wife, Katya Dolgorukova, in the summer of 1859, while visiting Prince Dolgorukov on the Teplovka estate. Soon, Catherine’s father went bankrupt and died, and her mother with four sons and two daughters found herself without funds. The Emperor took the children into his care: he facilitated the entry of the Dolgoruky brothers into St. Petersburg military institutions, and the sisters into the Smolny Institute. On March 28, 1865, Palm Sunday, Alexander II visited the Smolny Institute, where 18-year-old Ekaterina Dolgorukova was introduced to him. They began meeting secretly in the Summer Garden near the Winter Palace. On July 13, 1866, they met for the first time at Belvedere Castle near Peterhof, where they spent the night, after which they continued dating there.

At that time, Empress Maria Alexandrovna was already sick with consumption and did not get out of bed. The adulterous relationship caused acute displeasure among many Romanovs and, above all, the Tsarevich, the future Alexander III. By the end of the year, the Emperor was forced to send his mistress, accompanied by her brother, to Naples, followed by a visit to Paris, where they met in June 1867 in a hotel under the secret supervision of the French police.

During their relationship, Dolgorukova gave birth to three children to Alexander: a son, George, and two daughters, Olga and Ekaterina. Following the death of his wife on May 22, 1880, before the expiration of the protocol mourning period, on July 6, 1880, a wedding took place in the military chapel of the Tsarskoye Selo Palace, performed by Protopresbyter Xenophon Nikolsky.

Hobbies

Alexander II loved hunting. According to the classification of that time, hunters were divided into efficient, true, field and stupid. To be efficient meant: to take care of your dogs, to be quick-witted, dexterous and in no case a liar. Never appropriate someone else's animal, do not be greedy and do not run around in vain in the forest. Alexander II was considered the most efficient hunter of the Romanovs. Despite the fact that in the imperial dog hunting of Alexander II there were standard specimens of hunting dogs of various breeds, Alexander Nikolaevich loved Milord most of all. A detailed description of Milord as a representative of the hunting dog breed is given by the famous writer L. Sabaneev: “I saw the Imperial black dog in Ilyinsky after dinner, to which the sovereign invited members of the board of the Moscow Hunting Society. It was a very large and very beautiful indoor dog, with a beautiful head, well dressed, but there was little of the setter type in it, moreover, the legs were too long, and one of the legs was completely white. They say that this setter was given to the late emperor by some Polish gentleman, and there was a rumor that the dog was not entirely blood-born.”

Enemies

When asked whether Alexander II had enemies, we can say with confidence: yes. There were at least six attempts on his life alone.

The first attempt took place on April 4, 1866. Alexander II went for a walk with his nephews in the Summer Garden. Having enjoyed the fresh air, the tsar was already getting into the carriage when a young man came out from the crowd of onlookers watching the sovereign’s walk and shot at him, but missed. The shooter turned out to be nobleman Dmitry Karakozov. He called the motive for the assassination attempt the tsar’s deception of his people by the reform of 1861, in which, according to him, the rights of the peasants were only declared, but not actually implemented.

But it was not only in Russia that the sovereign was in danger. In June 1867, Alexander II arrived on an official visit to France. On June 6, after a military review at the Longchamps racecourse, he was returning in an open carriage with his children and a French Emperor Napoleon III. In the area of the Bois de Boulogne, among the jubilant crowd, a short, black-haired man, Anton Berezovsky, a Pole by origin, was already waiting for the official procession to appear. When the royal carriage appeared nearby, he fired a pistol at Alexander II twice. Thanks to the brave actions of one of Napoleon III’s security officers, who noticed a man with a weapon in the crowd in time and pushed his hand away, the bullets flew past the Russian Tsar, hitting only the horse. This time the reason for the assassination attempt was the desire to take revenge on the Tsar for the suppression of the Polish uprising of 1863.

The third attempt took place on April 4, 1879: the sovereign was walking in the vicinity of his palace. Suddenly he noticed a young man walking quickly towards him. The stranger managed to shoot five times before he was captured by security. On the spot they found out that the attacker was teacher Alexander Solovyov. At the investigation, he, without hiding his pride, stated: “The idea of an attempt on the life of His Majesty arose in me after becoming acquainted with the teachings of the socialist revolutionaries. I belong to the Russian section of this party, which believes that the majority suffers so that the minority can enjoy the fruits of the people’s labor and all the benefits of civilization that are inaccessible to the majority.”

If the first three attempts on the life of Alexander II were carried out by unprepared individuals, then since 1879 the goal of destroying the Tsar has been set by an entire terrorist organization - “People's Will”. Having analyzed previous attempts to kill the Tsar, the conspirators came to the conclusion that the surest way would be to organize an explosion of the Tsar’s train when the Tsar was returning from vacation from Crimea to St. Petersburg. But this time too the conspirators were defeated. Once again, heavenly forces intervened in the fate of Alexander II. The Narodnaya Volya knew that the imperial cortege consisted of two trains: Alexander II himself and his retinue were traveling in one, and the royal luggage in the second. Moreover, the train with luggage is half an hour ahead of the royal train. However, in Kharkov, one of the locomotives of the baggage train broke down - and the royal train went first. Not knowing about this circumstance, the terrorists let the first train through, detonating a mine under the fourth carriage of the second. Having learned that he had once again escaped death, Alexander II, according to eyewitnesses, sadly said: “What do they have against me, these unfortunates? Why are they chasing me like a wild animal? After all, I have always strived to do everything in my power for the good of the people!”

The “unhappy” people, not particularly discouraged by the failure of the railway epic, after some time began preparing a new assassination attempt. The Executive Committee decided to blow up the emperor's chambers in the Winter Palace. The explosion was scheduled for six twenty minutes in the evening, when Alexander II was supposed to be in the dining room. And again, chance confused all the cards for the conspirators. The train of one of the members of the imperial family - the Prince of Hesse - was half an hour late, delaying the time of the gala dinner. The explosion found Alexander II near the security room, located near the dining room.

After the explosion in Zimny, Alexander II began to rarely leave the palace, regularly going only to change the guard at the Mikhailovsky Manege. The conspirators decided to take advantage of this punctuality of the emperor. The security department warned the tsar more than once about the impending assassination attempt. He was advised not to travel to the Manezh and not to leave the walls of the Winter Palace. To all the warnings, Alexander II replied that he had nothing to fear, since he firmly knew that his life was in the hands of God, thanks to whose help he survived the previous five assassination attempts.

On March 1, 1881, Alexander II left the Winter Palace for Manege. Having attended the guard duty and having tea with his cousin, the Tsar went back to Zimny through... the Catherine Canal. The royal cortege drove to the embankment. Further events developed almost instantly. The terrorist Rysakov threw his bomb towards the royal carriage. There was a deafening explosion. After traveling some distance, the royal carriage stopped. The Emperor was not injured. However, instead of leaving the scene of the assassination attempt, Alexander II wished to see the criminal. He approached the captured Rysakov... At this moment, Grinevitsky, unnoticed by the guards, throws a second bomb at the Tsar’s feet. The blast wave threw Alexander II to the ground, blood gushing from his crushed legs. With the last of his strength, he whispered: “Take me to the palace... There I want to die...”.

On March 1, 1881, at 15:35, the imperial standard was lowered from the flagpole of the Winter Palace, notifying the population of St. Petersburg about the death of Emperor Alexander II.

Companions

Loris-Melikov can be called a true ally of Alexander II. Together they prepared a draft constitution, wanting to radically change the future of Russia. They saw Russia as a great power moving with the times. Loris-Melikov’s plans included a broad program for modernizing the state and public life of Russia. In the 70s, the tsar decided that pacification had arrived and appointed Mikhail Tarielovich Minister of Internal Affairs. It was then that Loris-Melikov began to prepare a draft document, which, for tactical reasons, was not called the word “constitution”, so as not to aggravate relations with reactionary circles in the government and at court. Mikhail Tarielovich considered it fundamentally important to take the first step in limiting autocracy. This document was already ready for publication. But within a day of this, a fatal bomb interrupted the life of the emperor, forever canceling out Loris-Melikov’s plans. Perhaps the 1917 revolution would never have happened if Russia had become a constitutional monarchy at the end of the 19th century.

Weaknesses

“Alexander’s main weakness as a political figure was that all his life human problems were more important to him than state ones. This was his weakness, but also his superiority: he was, first of all, a kind and noble man, and often his heart took precedence over his mind. Unfortunately, for a person destined by fate to be the ruler of Russia, this was rather a disadvantage,” says historian Vsevolod Nikolaev, and it is difficult to disagree with him.

Strengths

Emperor Alexander II was rightly awarded the “title” of Tsar-Liberator: he freed not only the peasants, but the personality of the Russian people in general, putting it in conditions of independent existence and development. Previously, the personality was suppressed and absorbed: in the most distant times - by the tribal life, later - by the state, which it had to serve, for which it had to exist. Now the state ceases to be a goal, it itself turns into an official body, into a means for the free development of the individual and the satisfaction of his material and spiritual needs.

Merits and failures

The great merit of Alexander II can be called the five reforms he carried out: peasant, zemstvo, judicial, urban and military; together with the abolition of corporal punishment, they constitute the inalienable glory and pride of the emperor’s reign. “The peasant reform, despite all its imperfections, was a colossal step forward; it was also the greatest merit of Alexander himself, who during the years of its development withstood with honor the onslaught of feudal and reactionary aspirations and at the same time revealed such firmness that those around him apparently did not count on” (Kornilov). “With wise determination, following the instructions of the times, Emperor Alexander II left the traditional path of discussing reform in secret committees and called on society itself to develop the intended transformation, and then, vigilantly monitoring the progress of reform work, with extreme tact, chose the time and external forms for declaring his personal views on one side or another of peasant affairs. If the art of ruling consists in the ability to correctly determine the urgent needs of a given era, to open a free outlet for viable and fruitful aspirations lurking in society, from the height of wise impartiality to pacify mutually hostile parties with the power of reasonable agreements, then one cannot but admit that Alexander Nikolaevich correctly understood the essence of his calling in memorable (1855-1861) of his reign. He firmly maintained his post at the “stern of his native ship” during these difficult years of his voyage, rightfully earning the inclusion of the enviable epithet Liberator to his name” (Kiesewetter).

The classless zemstvo and the classless city, attracting different classes of the population to common work for the common benefit, significantly contributed to the consolidation of individual groups and social classes into a single state body, where “one for all, and all for one.” In this regard, the zemstvo and city reforms were as great a national cause as the peasant reform. They put an end to the predominance of the nobility, democratized Russian society, and attracted new and more diverse layers of society to common work for the benefit of the state.

Judicial reform, in turn, had enormous cultural significance in Russian life. Set up independently of external and random influences, enjoying public trust, ensuring the population in the fair enjoyment of their rights, protecting these rights or restoring them in case of violation, the new court educated Russian society in respect for the law, for the personality and interests of their neighbors, and elevated people in their own eyes, served as a restraining principle equally for both the rulers and the subordinates.

The military reform, inseparably associated with the name of Milyutin, is entirely imbued with the spirit of liberation and humanity. It complemented other great reforms and, together with them, created a new era in Russian history from the reign of Alexander II. The same can be said about the abolition of corporal punishment. The decree of April 17, 1863 had enormous educational significance, since the old whip and girders taught people to cruelty, made them indifferent to the suffering of others; Fist reprisals and punishment with canes, often arbitrary, belittled a person’s personality: it embittered some, while others, on the contrary, were deprived of self-esteem.

The failures of Alexander II include the fact that none of the above reforms were ever completed. But it is worth mentioning that in the entire history of Russia, not a single ruler has yet managed to fully implement his reforms.

Alexander II conducted his foreign policy quite successfully. In 1872 he joined the Alliance of the Three Emperors, which became the cornerstone of Russian foreign policy until the Franco-Russian Alliance in 1893. In 1877, Turkish policies led to the Russo-Turkish War, which ended in Russian victory in 1878. Under Alexander II, the annexation of the Caucasus was completed. Russia expanded its influence in the east; it included Turkestan, the Amur region, the Ussuri region, and the Kuril Islands in exchange for the southern part of Sakhalin.

Compromising evidence

Alexander II loved Ekaterina Dolgorukova so boundlessly that he settled her and her children in the Winter Palace during the life of his first wife, which further exacerbated the hostility of many Romanovs towards her. The court was divided into two parties: supporters of Dolgorukova and supporters of the heir Alexander Alexandrovich. Such an act by Alexander II was unheard of insolence. Only he could afford to openly house his wife and mistress under one roof.

KM.RU April 29, 2008

March 13 (March 1, Old Style) - Memorial Day Tsar-Liberator Alexander II Nikolaevich , who became a victim of revolutionary terrorists on March 1, 1881.

He was born on April 17, 1818, on Bright Wednesday, in the Bishop's House of the Chudov Monastery in the Kremlin. His teacher was the poet V.A. Zhukovsky, who instilled in him a romantic attitude to life.

According to numerous testimonies, in his youth he was very impressionable and amorous. So, during a trip to London in 1839, he fell in love with the young Queen Victoria (later, as monarchs, they experienced mutual hostility and enmity).

In 1837, Alexander made a long trip around Russia and visited 29 provinces of the European part, Transcaucasia and Western Siberia, and in 1838-1839 he visited Europe.

Alexander never, either in his youth or in his mature years, adhered to any particular theory or concept in his views on the history of Russia and the tasks of public administration. His general views were characterized by the idea of the inviolability of the autocracy and the existing statehood of Russia as a stronghold of its unity, and of the divine origin of tsarist power. He confesses to his father, having become acquainted with Russia on a trip: “I consider myself lucky that God has assigned me to devote my entire life to her”. Having become an autocrat, he identified himself with Russia, considering his role, his mission as serving the sovereign greatness of the Fatherland.

Personal life

The personal life of Alexander II was unsuccessful. In 1841, at the insistence of his father, he married Princess Maximilian Wilhelmina Augusta Sophia Maria (†1880) of Hesse-Darmstadt. They had 7 children: Alexandra, Nicholas, Alexander (future Emperor Alexander III), Vladimir, Maria, Sergei, Pavel (the first two died: daughter in 1849, heir to the throne in 1865).

Tsar's wife Maria Alexandrovna

German by birth, Maria Alexandrovna was obsessed with her aristocracy. She did not love or respect Russia, did not understand or appreciate her husband, and spent most of her time embroidering or knitting and gossiping about court romances, intrigues, weddings and funerals at the courts of Europe. Alexander was not satisfied with such a wife. In 1866, he fell in love with Princess Ekaterina Dolgorukaya (†1922), whom he married immediately after the death of his first wife in 1880 in a morganatic marriage (a marriage between persons of unequal status in which the spouse of a lower status does not receive the same high social status as a result of this marriage). From this marriage he had 4 children.

Beginning of the reign

Alexander II ascended the throne at the age of 36 after the death of his father, Emperor Nicholas I, on February 19, 1855. The coronation took place in the Assumption Cathedral of the Kremlin on August 26, 1856. (the ceremony was led by Metropolitan of Moscow Filaret (Drozdov)). The full title of the emperor sounded like Emperor and Autocrat of All Russia, Tsar of Poland and Grand Duke of Finland. On the occasion of the coronation, the Emperor declared an amnesty for the Decembrists, Petrashevites, and participants in the Polish uprising of 1830-31.

Alexander II's accession to the throne occurred under very difficult circumstances. Finances were extremely upset by the unsuccessful Crimean War, during which Russia found itself in complete international isolation (Russia was opposed by the combined forces of almost all the major European powers). The first important step was conclusion of the Peace of Paris (1856) - on conditions that were not the worst in the current situation(in England there were strong sentiments to continue the war until the complete defeat and dismemberment of the Russian Empire). Thanks to some diplomatic moves,Alexander II succeededbreak the foreign policy blockade of Russia. Representatives of seven powers (Russia, France, Austria, England, Prussia, Sardinia and Turkey) gathered in Paris. Sevastopol was given to Russia, but the tsar was obliged not to establish a fleet in the Black Sea. I had to accept this condition, which was terribly humiliating for Russia. The Paris peace, although not beneficial for Russia, was still honorable for her in view of such numerous and strong opponents.

Reforms of Alexander II

.jpg)

Alexander II went down in history as a reformer and liberator (in connection with the abolition of serfdom according to the manifesto of February 19, 1861). He abolished corporal punishment and banned caning of soldiers. Before him, soldiers served for 25 years, soldiers' children were enlisted as soldiers from birth. Alexander introduced universal conscription, extending it to all nationalities, whereas previously only Russians served.

The state bank, loan offices, railways, telegraphs, government mail, factories, factories - everything arose under Alexander II, as well as urban and rural public schools.

During his reign, serfdom was abolished (1861) . The liberation of the peasants was the cause of a new Polish uprising in 1863. Transforming Russia, Alexander set the Russification of the outskirts - Finland, Poland and the Baltic region - as the cornerstone of the transformation.

GREAT REFORM OF ALEXANDER II

Assessments of some of Alexander II's reforms are contradictory. The liberal press called his reforms “great.” At the same time, a significant part of the population (part of the intelligentsia), as well as a number of government officials of that era, negatively assessed these reforms.

Foreign policy

During the reign of Alexander II, Russia returned to the policy of all-round expansion of the Russian Empire, previously characteristic of the reign of Catherine II.

During this period, Central Asia, the North Caucasus, the Far East, Bessarabia, and Batumi were annexed to Russia. Victories in the Caucasian War were won in the first years of his reign. The advance into Central Asia ended successfully (in 1865-1881, most of Turkestan became part of Russia).

On the eastern outskirts of Asia, during the reign of Alexander II, Russia also made quite important acquisitions, and also peacefully. According to the treaty with China (1857), the entire left bank of the Amur went to Russia, and the Beijing treaty (1860) also provided us with part of the right bank between the river. Ussuri, Korea and the sea. Since then, the rapid settlement of the Amur region began, and various settlements and even cities began to emerge one after another.

Under Alexander II, the “deal of the century” took place on the sale of Alaska. In 1867, the government decided to give up Russia's possessions in North America and sold Alaska (Russian America) to the United States for $7 million (by the way, a 3-story district court building in New York then cost more than all of Alaska).

In 1875, Japan ceded the part of Sakhalin that did not yet belong to Russia in exchange for the Kuril Islands.

But his main achievement was the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-1878, which brought liberation to the Balkan peoples from the Turkish yoke.

The Turks conquered the Balkan Peninsula and all Christians were enslaved. For 500 years, Greeks, Serbs, Bulgarians, Croats and Armenians languished under the yoke of Muslims. They were all slaves. Their property and lives belonged to the Turks. Their wives and daughters were taken away into harems, and their sons into slavery. Finally the Bulgarians rebelled. The Turks began to pacify them with brutal executions and torture. Alexander tried to achieve liberation peacefully, but in vain. Then Russia declared war on Turkey, and all Russians enthusiastically went to shed their blood for their Christian brothers. In 1877, the Balkan Slavs were liberated!

Growing public discontent

The reign of Alexander II, despite liberal reforms, was not calm. The economic situation of the country worsened: industry was struck by a protracted depression, and there were several cases of mass famine in the countryside.

The foreign trade deficit and public external debt reached large sizes (almost 6 billion rubles), which led to a breakdown in monetary circulation and public finances.

The problem of corruption has worsened.

A split and acute social contradictions formed in Russian society, which reached their peak towards the end of the reign.

Other negative aspects usually include the unfavorable results of the Berlin Congress of 1878 for Russia, exorbitant expenses in the war of 1877-1878, numerous peasant uprisings (in 1861-1863: more than 1150 uprisings), large-scale nationalist uprisings in the kingdom of Poland and the North-Western region (1863) and in the Caucasus (1877-1878).

Assassination attempts

Under Alexander II, the revolutionary movement developed strongly. Members of revolutionary parties made attempts on the tsar's life several times.

The terrorists organized a real hunt for the Emperor. There have been multiple attempts on his life: Karakozov April 4, 1866 , Polish emigrant Berezovsky May 25, 1867 in Paris, Soloviev April 2, 1879 in St. Petersburg, an attempt to blow up an imperial train near Moscow November 19, 1879 , explosion in the Winter Palace carried out by Khalturin February 5, 1880 .

According to rumors, in 1867, a Parisian gypsy told the Russian Emperor Alexander II: “Six times your life will be in the balance, but will not end, and the seventh time death will overtake you.” The prediction came true...

Murder

March 1, 1881 - the last attempt on Alexander II's life, which led to his death.

The day before, February 28 (Saturday of the first week of Lent), the emperor, in the Small Church of the Winter Palace, together with some other family members, received the Holy Mysteries.

Early in the morning of March 1, 1881, Alexander II left the Winter Palace for the Manezh, accompanied by a rather small guard. He was present at the changing of the guards and, after drinking tea with his cousin, Grand Duchess Catherine Mikhailovna, the emperor went back to the Winter Palace through the Catherine Canal. The assassination attempt occurred when the royal motorcade drove onto the embankment of the Catherine Canal in St. Petersburg. Nikolai Rysakov was the first to throw a bomb, but the tsar was not injured (this was the sixth unsuccessful attempt). He got out of the carriage and spoke to the Narodnaya Volya member, asking his name and rank. At that moment, Ignatius Grinevitsky ran up to Alexander II and threw a bomb between himself and the tsar. Both were mortally wounded. The blast wave threw Alexander II to the ground, bleeding profusely from his crushed legs. The fallen emperor whispered: “Take me to the palace... There I want to die.” Alexander II was put in a sleigh and sent to the palace. There, after some time, Alexander II died.

In the hospital, before his death, the regicide came to his senses, but did not give his last name. Rysakov was unharmed and was immediately arrested and interrogated by investigators. Fearing a death sentence, the 19-year-old terrorist told everything he knew, including betraying the entire core of Narodnaya Volya. Arrests of the organizers of the assassination began. At the trial of the “First Marchers” Grinevitsky was treated as Kotik, Elnikov or Mikhail Ivanovich. The real name of the king's killer became known only in  Soviet time. Oddly enough, this young man was not a “fiend of hell” in life. Ignatius Joachimovich Grinevitsky was born in the Minsk province in 1856 into the family of an impoverished Polish nobleman. He successfully graduated from the Bialystok Real Gymnasium and in 1875 entered the Technological Institute of St. Petersburg. Everyone knew him as a gentle, modest, friendly person with a highly developed sense of justice. At the gymnasium, Ignatius was one of the best students and there he received the nickname Kotik, which later became his underground nickname. At the institute, he joined a revolutionary circle, was one of the organizers of the publication of the Workers' Newspaper, and a participant in the “walk among the people.” According to evidence, Grinevitsky not only had a gentle disposition, but was also a Catholic. It’s hard to wrap my head around how a Christian believer could commit murder. Obviously, he believed that autocracy in Russia is a great evil, all means are good to destroy it, and he professed conscious self-sacrifice with a willingness to give himself “into the hands of the devil.” What was it? The greatest ideological spirit or simply clouding of the mind?

Soviet time. Oddly enough, this young man was not a “fiend of hell” in life. Ignatius Joachimovich Grinevitsky was born in the Minsk province in 1856 into the family of an impoverished Polish nobleman. He successfully graduated from the Bialystok Real Gymnasium and in 1875 entered the Technological Institute of St. Petersburg. Everyone knew him as a gentle, modest, friendly person with a highly developed sense of justice. At the gymnasium, Ignatius was one of the best students and there he received the nickname Kotik, which later became his underground nickname. At the institute, he joined a revolutionary circle, was one of the organizers of the publication of the Workers' Newspaper, and a participant in the “walk among the people.” According to evidence, Grinevitsky not only had a gentle disposition, but was also a Catholic. It’s hard to wrap my head around how a Christian believer could commit murder. Obviously, he believed that autocracy in Russia is a great evil, all means are good to destroy it, and he professed conscious self-sacrifice with a willingness to give himself “into the hands of the devil.” What was it? The greatest ideological spirit or simply clouding of the mind?

The death of the “Liberator”, killed by the Narodnaya Volya on behalf of the “liberated”, seemed to many to be a symbolic end of his reign, which led, from the point of view of the conservative part of society, to rampant “nihilism”. They say that half of Russia wanted him dead. Right-wing politicians said that the emperor died “at the right time”: if he had reigned for another year or two, the catastrophe of Russia (the collapse of the autocracy) would have become inevitable.

Demons- so F.M. Dostoevsky called revolutionaries terrorists. In his last work, The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoevsky wanted to continue the theme of Demons. The writer planned to “make” Alyosha Karamazov, almost a saint, a terrorist who ended his life on the scaffold! Dostoevsky is often called a prophet-writer. Indeed, he not only predicted, but even described the future killer of the Tsar: Alyosha Karamazov is very similar to Ignatius Grinevitsky. The writer did not live to see the assassination of Alexander II - he died a month before the tragic event.

Despite the arrest and execution of all the leaders of Narodnaya Volya, terrorist acts continued in the first 2-3 years of the reign of Alexander III.

Results of the reign of Alexander II

Alexander II left a deep mark on history; he managed to do what other autocrats were afraid to undertake - the liberation of peasants from serfdom. We still enjoy the fruits of his reforms to this day. During his reign, Russia firmly strengthened its relations with European powers and resolved numerous conflicts with neighboring countries. The internal reforms of Alexander II are comparable in scale only to the reforms of Peter I. The tragic death of the emperor greatly changed the further course of history, and it was this event that, 35 years later, led Russia to death, and Nicholas II to a martyr’s wreath.

The views of modern historians on the era of Alexander II were subject to dramatic changes under the influence of the dominant ideology, and are not settled.

Material prepared by Sergey Shulyak

Alexander II Nikolaevich (Alexander Nikolaevich Romanov; April 17, 1818 Moscow - March 1 (13), 1881 St. Petersburg)

Alexander II

The eldest son of first the grand ducal, and since 1825, the imperial couple Nicholas I and Alexandra Feodorovna, daughter of the Prussian king Frederick William III.

Born on April 17, 1818, on Bright Wednesday, at 11 o'clock in the morning in the Bishop's House of the Chudov Monastery in the Kremlin, where the entire Imperial family, excluding the uncle of the newborn Alexander I, who was on an inspection trip to the south of Russia, arrived in early April for fasting and celebrating Easter; A 201-gun salvo was fired in Moscow. On May 5, the sacraments of baptism and confirmation were performed over the baby in the church of the Chudov Monastery by Moscow Archbishop Augustine, in honor of which Maria Feodorovna gave a gala dinner.

The future emperor was educated at home. His mentor (with the responsibility of supervising the entire process of upbringing and education) was the poet V.A. Zhukovsky, teacher of the Law of God and Sacred History - Archpriest Gerasim Pavsky (until 1835), military instructor - Karl Karlovich Merder, and also: M.M. Speransky (legislation), K. I. Arsenyev (statistics and history), E. F. Kankrin (finance), F. I. Brunov (foreign policy), Academician Collins (arithmetic), K. B. Trinius (natural history) .

According to numerous testimonies, in his youth he was very impressionable and amorous. So, during a trip to London in 1839, he had a fleeting, but strong, love for the young Queen Victoria, who would later become for him the most hated ruler in Europe.

Upon reaching adulthood on April 22, 1834 (the day he took the oath), the Heir-Tsarevich was introduced by his father into the main state institutions of the Empire: in 1834 into the Senate, in 1835 he was introduced into the Holy Governing Synod, from 1841 a member of the State Council, in 1842 - the Committee ministers.

In 1837, Alexander made a long trip around Russia and visited 29 provinces of the European part, Transcaucasia and Western Siberia, and in 1838-39 he visited Europe.

The military service of the future emperor was quite successful. In 1836 he already became a major general, and from 1844 a full general, commanding the guards infantry. Since 1849, Alexander was the head of military educational institutions, chairman of the Secret Committees on Peasant Affairs in 1846 and 1848. During the Crimean War of 1853-56, with the declaration of martial law in the St. Petersburg province, he commanded all the troops of the capital.

In his life, Alexander did not adhere to any particular concept in his views on the history of Russia and the tasks of public administration. Having ascended the throne in 1855, he received a difficult legacy. None of the issues of his father’s 30-year reign (peasant, eastern, Polish, etc.) were resolved; Russia was defeated in the Crimean War.

The first of his important decisions was the conclusion of the Paris Peace in March 1856. A “thaw” has set in in the socio-political life of the country. On the occasion of his coronation in August 1856, he declared an amnesty for the Decembrists, Petrashevites, and participants in the Polish uprising of 1830-31, suspended recruitment for 3 years, and in 1857 liquidated military settlements.

Not being a reformer by vocation or temperament, Alexander became one in response to the needs of the time as a man of sober mind and good will.

Alexander II

In a reference article, it is inappropriate to evaluate the results of the complex and contradictory reform activities of Alexander II. At the moment we are interested in, only one reform has become a fact (but what a reform!) - the peasant reform. But its practical implementation has only just begun. For details of the peasant reform, see the articles already posted earlier.

Next, I refer those interested to a rather good popular journalistic book: L. Lyashenko. Alexander II, or the story of three solitudes

***

Maria Alexandrovna (August 8, 1824, Darmstadt - June 8, 1880, St. Petersburg) - wife of the Russian Emperor Alexander II and mother of the future Emperor Alexander III.

Born Princess Maximilian Wilhelmina Maria of Hesse (1824-1841), after her marriage she received the title of Grand Duchess (1841-1855), after her husband's accession to the Russian throne she became empress (March 2, 1855 - June 8, 1880).

Mary was the illegitimate daughter of Wilhelmine of Baden, Grand Duchess of Hesse and her chamberlain Baron von Sénarclin de Grancy. Wilhelmina's husband, Grand Duke Ludwig II of Hesse, to avoid scandal and thanks to the intervention of Wilhelmina's siblings, recognized Maria and her brother Alexander as his children (the other two illegitimate children died in infancy). Despite the recognition, they continued to live separately in Heiligenberg, while Ludwig II lived in Darmstadt.

Empress Maria Alexandrovna

In 1838, the future Emperor Alexander II, traveling around Europe to find a wife, fell in love with 14-year-old Maria of Hesse and married her in 1841, although he was well aware of the secret of her origin.

Wedding silver ruble of Nicholas I for the wedding of the heir to the throne Alexander Nikolaevich and Princess Maria of Hesse

On the initiative of Maria Alexandrovna, all-class women's gymnasiums and diocesan schools were opened in Russia, and the Red Cross was established.

Cities in Russia were named in honor of Maria Alexandrovna:

Mariinsky Posad (Chuvashia). Until 1856 - the village of Sundyr. On June 18, 1856, Emperor Alexander II renamed the village to the city of Mariinsky Posad in honor of his wife.

Mariinsk (Kemerovo region). Renamed in 1857 (former name - Kiyskoe).

Here it is website(school local history museum), dedicated to Maria Alexandrovna.

* * *

At the point in time that interests us, the heir to the throne is considered... no, not the future Emperor Alexander III. And the eldest son of Alexander II is Nikolai Alexandrovich.

Nikolai Alexandrovich (8 (20) September 1843 - 12 (24) April 1865, Nice) - Tsarevich and Grand Duke, eldest son of Emperor Alexander II, ataman of all Cossack troops, major general of His Imperial Majesty's retinue, chancellor of the University of Helsingfors.

Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich

In the early 1860s, accompanied by his tutor Count S.G. Stroganov, he made study tours around the country. In 1864 he went abroad. While abroad, on September 20, 1864, he was engaged to the daughter of Christian IX, King of Denmark, Princess Dagmar (1847-1928), who later became the wife of his brother, Emperor Alexander III. While traveling in Italy, he fell ill and died of tuberculous meningitis.

Heir Tsarevich Nikolai Alexandrovich with his bride, Princess Dagmara

* * *

In total, at the time we are interested in, the imperial couple had seven children (and a total of 8 children were born in the family)

The first child of the future Emperor Alexander II and Maria Alexandrovna, Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna, was born in 1842 and died suddenly at the age of seven. After her death, no one in the imperial family named their daughters after Alexander, since all the princesses with that name died early, before reaching the age of 20.

Second child - Nikolai Alexandrovich, Tsarevich (see above)

The third is Alexander Alexandrovich, the future Emperor Alexander III (born in 1845)

Further:

Vladimir (born in 1847)

Alexey (born in 1850)

Maria (born in 1853)

Sergei (born in 1857) (the same one who would later be killed by the Socialist-Revolutionary terrorist Ivan Kalyaev in 1905)

Pavel (born in 1860)

At least two other members of the imperial family played a major role in carrying out the Great Reforms: Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich and Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna.

Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich (September 9, 1827 St. Petersburg - January 13, 1892 Pavlovsk) - the second son of the Russian Emperor Nicholas I.

His father decided that Konstantin should become almiral of the fleet and, from the age of five, entrusted his upbringing to the famous navigator Fyodor Litka. In 1835 he accompanied his parents on a trip to Germany. In 1844 he was appointed commander of the brig Ulysses, in 1847 - the frigate Pallada. On August 30, 1848 he was appointed to the retinue of His Imperial Majesty and chief of the Naval Cadet Corps.

In 1848 in St. Petersburg he married Alexandra Friederike Henrietta Paulina Marianna Elisabeth, the fifth daughter of Duke Joseph of Saxe-Altenburg (in Orthodoxy Alexandra Iosifovna).

In 1849 he was appointed to sit on the State and Admiralty Councils. In 1850 he headed the Committee to revise and supplement the General Code of Naval Charter and became a member of the State Council and the Council of Military Educational Institutions. Promoted to vice admiral in 1853. During the Crimean War, Konstantin Nikolaevich took part in the defense of Kronstadt from the attack of the Anglo-French fleet.

Since 1855 - admiral of the fleet; from that time on he managed the fleet and the maritime department as a minister. The first period of his management was marked by a number of important reforms: the previous sailing fleet was replaced by a steam one, the available composition of coastal teams was reduced, office work was simplified, and emerital cash desks were established; Corporal punishment has been abolished.

Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolaevich

He adhered to liberal values, and in 1857 he was elected chairman of the peasant committee that developed reform projects.

Viceroy of the Kingdom of Poland from June 1862 to October 1863. His viceroy fell on the period before and during the January Uprising. Together with the civil governor of the CPU, Marquis Alexander Wielopolsky, he tried to pursue a conciliatory policy and carry out liberal reforms, but without success. Soon after Konstantin Nikolaevich arrived in Warsaw, an attempt was made on his life. Journeyman tailor Ludovic Yaroshinsky shot him point-blank with a pistol on the evening of June 21 (July 4), 1862, when he was leaving the theater, but Konstantin Nikolaevich was only slightly wounded. (more details about the events in the Central Election Commission on the eve of the January Uprising will be discussed in a separate article)

* * *

A truly outstanding person was Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, widow of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich (younger brother of Alexander I and Nicholas I).

Before accepting Orthodoxy - Princess Frederike Charlotte Marie of Württemberg (German: Friederike Charlotte Marie Prinzessin von Württemberg, December 24 (January 6) 1806 - January 9 (22), 1873)

Princess of the House of Württemberg, daughter of Duke Paul Karl Friedrich August and Princess of the Ducal House of Saxe-Altenburg Charlotte Dahlia Friederike Louise Sophia Theresa.

She was brought up in Paris at the private boarding house Campan.

At the age of 15, she was chosen by the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, also a representative of the House of Württemberg, as the wife of Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich, the fourth son of Emperor Paul I.

She converted to Orthodoxy and was granted the title of Grand Duchess as Elena Pavlovna (1823). On February 8 (21), 1824, she was married according to the Greek-Eastern Orthodox rite with Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich.

In 1828, after the death of the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, according to Her Highest will, control of the Mariinsky and Midwifery Institutes passed to the Grand Duchess. She was the chief of the 10th Dragoon Novgorod Regiment.

She showed herself as a philanthropist: she gave funds to the artist Ivanov to transport the painting “The Appearance of Christ to the People” to Russia, and patronized K. P. Bryullov, I. K. Aivazovsky, and Anton Rubinstein. Having supported the idea of establishing the Russian Musical Society and Conservatory, she financed this project by making large donations, including proceeds from the sale of diamonds that personally belonged to her. The conservatory's primary classes opened in her palace in 1858.

She supported the actor I. F. Gorbunov, the tenor Nilsky, and the surgeon Pirogov. She contributed to the posthumous publication of the collected works of N. V. Gogol. She was interested in the activities of the university, the Academy of Sciences, and the Free Economic Society.

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna

In 1853-1856 she was one of the founders of the Holy Cross community of sisters of mercy with dressing stations and mobile hospitals - the community charter was approved on October 25, 1854. She issued an appeal to all Russian women not bound by family responsibilities, calling for help for the sick and wounded. The premises of the Mikhailovsky Castle were provided at the disposal of the community for storing things and medicines; the Grand Duchess financed its activities. In the fight against the views of society, which did not approve of this kind of activity by women, the Grand Duchess went to hospitals every day and bandaged the wounded with her own hands.

For the cross that the sisters were to wear, Elena Pavlovna chose St. Andrew's ribbon. On the cross there were inscriptions: “Take My yoke upon you” and “You, O God, are my strength.” Elena Pavlovna explained her choice like this: “Only in humble patience do we receive strength and strength from God.”

On November 5, 1854, after mass, the Grand Duchess herself put a cross on each of the thirty-five sisters, and the next day they left for Sevastopol, where Pirogov was waiting for them.

On N.I. Pirogov, the great Russian scientist and surgeon, was entrusted with training and then supervising their work in the Crimea. From December 1854 to January 1856, more than 200 nurses worked in Crimea.

After the end of the war, an outpatient clinic and a free school for 30 girls were additionally opened in the community.

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna among the sisters of mercy, mid-1850s

The Grand Duchess provided guardianship to the school of St. Helena; founded in memory of her daughters the Elisabeth Children's Hospital (St. Petersburg), and the Elisabeth and Mary orphanages (Moscow, Pavlovsk); reorganized the Maximilian Hospital, where, on her initiative, a permanent hospital was created.

Since the late 1840s, evenings were held in the Mikhailovsky Palace - “Thursdays” at which issues of politics and culture, literary novelties were discussed. The circle of Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, which met on “Thursdays,” became the center of communication for leading statesmen - the developers and conductors of the Great Reforms.

According to A. F. Koni, meetings with Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna were the main discussion platform where plans for reforms in the second half of the 19th century were developed. Supporters of reforms called her among themselves “the benefactor mother.”